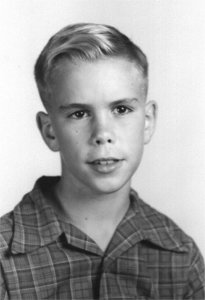

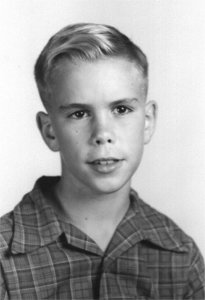

1954-1955.

|

|

Larry, about age 11, school picture, 1954-1955. |

I have often had this kind of excitement at or near many of our nation's bays and beaches, off the shores of New York, New Jersey, Virginia, South Carolina, Florida, Louisiana, Texas, Oregon, and Washington.

But, while growing up, the closest I came, apart from an officially spiritual setting, to a religious experience occurred in California, when I first encountered the Pacific Ocean. Our budding family, then including just Leon, Julia, myself, Jeanie, and the baby, John, was on a trip up the western coast of our country, about the winter of 1954 or 1955, on our way from San Antonio, Texas, to Washington State. We had, except for Dad, for close to a year been in San Antonio, near several of his relatives, including Papa Frank and Mama Pearl, his parents, Aunt Lucile and Uncle Shelby, his sister and his brother-in-law, and their children, my cousins, Bob and Marcile. Dad had been stationed in the Philippines, leaving for that tour of duty while the rest of his family was still living in the suburbs of Omaha, Nebraska. Mom had had some briefly harrowing adventures before we were safely established in Texas; but that is at least one more story. Leon, now back, had recently received his new orders and was about to start an assignment with the Air Force Office of Special Investigations (OSI).

I had an aunt, Mabel, another of Dad's sisters, then living in San Francisco. We had arranged to take a break from our driving trip to visit her there. I had certainly seen the ocean before; but it seemed that the last time had been years ago, while I was still too young to appreciate it, though, as with dream-like memories I still have of a beach in New Jersey, it had made a deep impression on me even as a toddler. Some of the experience I was to have now could have been augmented by my anticipation, which must have been all the more keen because of the long, often tense and tiring, trip we had had up till then. In any case, once we finally arrived in San Francisco, I could hardly wait. I knew that the Pacific was immense, our water planet's deepest and broadest sea. I had heard of its great tempests and exotic island cultures. I had been told that, despite its name, it often had truly fierce disturbances, particularly during the winter months.

At last, as we crested one of San Francisco's famous hills, the hugeness of this phenomenon, the vast, blue-gray Pacific Ocean, lay before me. I was amazed. No westward traveling 19th Century settler could have been more overwhelmed by the enormity of our country's prairies than I was on seeing that giant sea. A few minutes later we pulled up outside Aunt Mabel's bungalow, only a few short blocks up from the ever crashing surf. A mutt eager for an energetic walk could not have been more intense than I felt in my obsession to get down the road the rest of the way to the ocean. I endured the slow formalities of greeting Aunt Mabel and of our family's elaborate settling-in behaviors. Mabel seemed a very nice lady. It was pleasant to visit with her. But my ears were attuned only to the ocean's nearby roar. It was already afternoon and growing darker as the day wore on, the sky overcast or foggy. Our stay would be short. Dad and his sister did not get along all that well. In no time we would, the next day I believed, be on the road again. The sea Sirens beckoned. I could hardly contain my frustration, but had been taught to behave well, no matter what, always respecting my elders, never showing too much emotional display. The grown-ups were prattling. I think coffee was served and that I had a little. Decisions needed to be made about where each person was to sleep, what would be done about supper, etc. We had, of course, to find out how things had been for Mabel lately and for her to get acquainted or reacquainted with each of the young folks. A lot of polite chitchat went on, and on. The youngest child, John, needed to be looked after.

I was amazed. No westward traveling 19th Century settler could have been more overwhelmed by the enormity of our country's prairies than I was on seeing that giant sea. A few minutes later we pulled up outside Aunt Mabel's bungalow, only a few short blocks up from the ever crashing surf. A mutt eager for an energetic walk could not have been more intense than I felt in my obsession to get down the road the rest of the way to the ocean. I endured the slow formalities of greeting Aunt Mabel and of our family's elaborate settling-in behaviors. Mabel seemed a very nice lady. It was pleasant to visit with her. But my ears were attuned only to the ocean's nearby roar. It was already afternoon and growing darker as the day wore on, the sky overcast or foggy. Our stay would be short. Dad and his sister did not get along all that well. In no time we would, the next day I believed, be on the road again. The sea Sirens beckoned. I could hardly contain my frustration, but had been taught to behave well, no matter what, always respecting my elders, never showing too much emotional display. The grown-ups were prattling. I think coffee was served and that I had a little. Decisions needed to be made about where each person was to sleep, what would be done about supper, etc. We had, of course, to find out how things had been for Mabel lately and for her to get acquainted or reacquainted with each of the young folks. A lot of polite chitchat went on, and on. The youngest child, John, needed to be looked after.

I tried to entertain myself and Jeanie with crude little moving-picture drawings of slightly different designs on pages of a hand-held tablet, so that, by rolling up the top sheet along a quickly moving pencil, then spreading the sheet out rapidly again, the eyes were tricked into seeing the images move. "See what magic, Jeanie!"

At length (an interval of somewhere between thirty minutes and two to three hours, that felt close to eternity), I was given permission, after much instruction on how to find my way back, to walk down to the beach for a little while.

How I raced away! When I got to the strand, the sand was a wide expanse, unbroken, till mine intruded, by any footprints, as far in either side direction as I could see. It is perhaps unimaginable today that others were not there in droves. But it was the mid-1950s and winter as well. I saw no other people that afternoon.

There were birds aplenty. Here and there the smooth, wet surface was marred by huge long, stretched out stalks with peculiar yellow-brownish leaves that I would later learn were kelp, from great forests of them just offshore, that rose up from deep below, higher than most trees. There must have been a storm the night before, for many of these had broken loose and been washed up.

The brown-gray and white surf pounded the shore. My heart beat in sympathy, hardly able to contain my joy.

The sky was light gray, the wind sharp, cold, and cutting through my clothes. From the buffeted dunes I could look out far into the foggy distance at the edges of a sea that stretched before me for perhaps six thousand miles. My spirit soared. I felt as utterly insignificant before those waves as one of the sand grains. Yet I felt the kinship with a million, million present and past denizens of the deep. I felt the sweep of the ocean about and against the land, like a lover world-girdling in its embrace, stroking the never-ending shore. I felt at one with all I perceived and more. I felt the call and the breeze-lofted drifting of a thousand birds who could soar and see across the powerful winter current channels of Neptune and Poseidon's realm.

|

|

Mabel, Leon's oldest sister, about 1970, at Julia and Leon's 10-B Ranch, Austin, Texas. |

Back at Mabel's house, the evening wound down. Dad and she, long into the night, carried on a discussion that could have no happy ending, she insisting on the truth of astrology, he on a scientific answer to everything. Neither convinced the other. Each, terribly earnest and intent, stated her or his case with a score or a hundred different "proofs." Eventually, seemingly in the morning's wee hours, the argument ground down to an unsatisfactory conclusion and they went their separate ways to bed.

The next day we left for Washington, but not before I'd had one more, too short, sojourn by the sea, the morning sun breaking through the clouds and making the sand and surf seem to glow. This time, along with the pieces of kelp, I found newly deposited sand dollars and shells of all kinds. I gathered a dozen or more of these and stuffed them like newfound treasures into all my pockets.

Later, a day or two farther along in our trip, a rich, ripe odor began to suffuse our car. Investigations revealed it to have my shell collection as its origin. It turned out several of the shells had still been inhabited. Now their owners had begun to advertise their presence. I was disappointed that I had to throw most of them out.

As we proceeded on toward the awaiting adventures of the Pacific Northwest, Dad continued his arguments of the night before, with long and repeated justifications of his position. I wished he could have simply enjoyed the beautiful scenery through which we were passing. But still, it did not bother me much. I saw that, whether my life should now be long or short, it would feel complete. For a shimmering little while, I had become the sea.