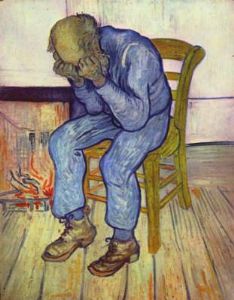

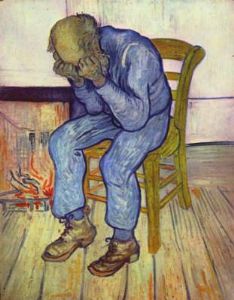

Old Man in Sorrow (On the Threshold of Eternity) by Van Gogh, 1890

Our staff at ASH, the EMS guys, and the Austin cop were all White. The man being admitted was Black, or a Negro, as we said then. I was a young Liberal with leanings toward being a pastor and several Civil Rights rallies or marches under my belt, and thought I had only good things to offer those I considered the less privileged in our society. Idealism was about to meet reality.

We would later learn that our John Doe - we never found out his name, and there was no wallet or other ID in his clothes - had probably been an insulin dependent diabetic and could have been having a sugar crisis, that temporarily affected his mental functioning, when he was picked up. I wondered afterward if something as easy as drinking a few ounces of orange juice might have quickly restored him to rational speech and behavior. Instead of going to a mental hospital, he may have merely needed help from a friend or, failing that, rapid emergency room attention. But the gendarme had noted he'd been acting strangely, so here he was.

Though ours was one of the few ASH wards that then routinely provided both psychiatric and traditional medical treatment, we were not staffed or prepared to give acute care. There was one rotating on-call physician, not on the premises. He would typically not arrive at the facility till about an hour or more after the medical center night nurse would phone him reporting a problem she could not handle on her own. Usually it would be a death or near death, and he would arrive in time to sign the final paperwork.

Each ward had just two assigned night orderlies, or ward attendants as we were known, per shift, but we made do with one if a colleague were late, out sick, or came in too drunk, as my partner there did on occasion, to do his job that night, and had to sleep it off in the office or in a spare patient bed.

Old Man in Sorrow (On the Threshold of Eternity) by Van Gogh, 1890 |

The job was full-time and paid take home wages of $131 a month when I started. Out of that we had to provide our own starched and clean white uniforms. There were no medical plans or perks. There were no meals, snacks, or coffee offered by the facility. Even in those days, that was not a very good pay and benefits package, but on the night shift there would sometimes be enough down time between rounds to get in a little studying, not that I ever felt like breaking open a book. My little room near campus, plus board, cost me more than half of the paycheck. There was not enough left over for an air-conditioned apartment. My place was on a top floor where the warm rising air collected, and, with the windows wide open, often never got cool enough for me to sleep properly during the day, even if I could have despite the noise from folks with a more normal schedule. I felt nearly overwhelming fatigue most of my time at ASH.

We were certainly not set up there to make diagnoses, except of the most rough and ready kind. Yet we did regularly take (and test) urine samples, temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, and other measurements, and we noted patient behavior and appearance, logging such info in the charts, officially each hour but actually at least once a shift. The chart records presumably were later read by the day shift nurses and doctors, to aid them in refining treatment approaches. Many patients, however, were just receiving rather custodial care and were left on our ward to die.

We could supposedly accommodate around 40 people per ward, four beds to a room with about ten rooms, but usually had less than that, probably about 25-30.

The physical and psychiatric medicine conditions of our patients were interesting and ran the gamut. There was one man with far advanced syphilis. He did not talk and acted as though he could no longer think as a human being. He would rock back and forth a lot, not keep his gown on, and frequently, on becoming excited, make noises similar to an upset chimpanzee.

Another patient had what my colleague, Jimmy, called "criminal insanity." I think he had paranoid schizophrenia. He reportedly had murdered a couple people, but was now supposedly under adequate control with large doses of Thorazine, though I saw him knock another patient senseless with a savage broom handle blow to the head. Asked why, he said he did not like roommates. After that he had a private room.

In my first month at ASH, we had a cute little boy patient. I never knew his mental problem. He had pneumonia. Less than a year old, he required frequent bottle feeding, diaper changes, social interaction, and cleaning of a really gross tracheotomy tube. I was told he was a welfare case, that none of the regular hospitals were willing to take him.

I think the same thing was true of a very engaging, amazingly upbeat, and quite lucid Black man with terminal cancer. The disease had spread throughout his lower torso region, with infected lesions through the abdominal wall.

There was a teenager periodically on our ward for recuperative care after each of his most recent surgeries. He liked to chew up and swallow razor blades and syringes, complete with needles. Such things were never to be left available to him, but he seemed to consider it a game and always managed sooner or later to find and down one, then would calmly report his latest "success." His upper alimentary canal was said to be a mass of scar tissue.

Saturno (Saturn Devouring One of His Children) by Goya, 1821-23 |

One man, born during the First World War, was permanently regressed to a behavioral age of about two months. My colleague, showing me around that first night, demonstrated his sadism by spanking this fat naked bedfast man, who instantly began to cry just as an infant would in the same circumstances, but with much greater lung capacity, sounding like an air raid siren.

Another fellow was obsessive compulsive to a degree rather more severe than my own tendencies. He would horde and then produce in quantity, measure, and roll his feces into golf ball sized surprises that he would hurl at us with great venom as we were walking down the hall past his room, always yelling out as loudly as he could "Gawd damn right!" as he would let fly.

One depressed man had severe tuberculosis and was at our location mainly because we had the facilities for keeping him in quarantined isolation. He was indeed mostly left alone. When entering his area to take care of routine needs, give him his meals, and at least say "Hello" from time to time, one had to wear a surgical mask and disposable gloves. I would have been depressed too.

An elderly gentleman felt impelled to slash up his penis. Lacking any more efficient instrument, he would use his fingernails. He had to be catheterized, have the traumatized member sewn up, and be restrained to keep him from messing with the sutures and dressings.

A man was eaten up with huge bed sore ulcers on his back and buttocks. These never healed but only got worse no matter what we did. He received, as a once per shift prescription, an ounce of pure alcohol, and seemed to live for that moment each several hours. His lips would begin a spasm of anticipatory puckering when he heard one of us coming toward his room at about the right time for this fix.

A boy there for a little while was a few years old but had the body of a toddler and a peculiarly large head due to hydrocephalus. He had not been properly treated for it, or not in time. Actually, I do not know if the current surgical treatment, a catheter under the skin, from the head into the stomach, to drain the extra liquid before it could cause such harrowing complications, had been developed or was in wide use yet, but if so it seems not to have been available to the indigent. Excess fluid had filled the cranial cavity, putting ever increasing pressure on the skull and the compromised brain, till he existed with but a fraction of it still functioning, his head so large in proportion to the rest of him that he had to have it held in place, lest, with a sudden movement, he would break his tiny neck and severe the spinal cord.

There was a catatonic schizophrenic patient who in my experience never was alert or interactive at all. He was almost perpetually in the fetal position. Even his breathing and pulse were reduced to a bare minimum and were usually not detectable. We would take his rectal temperature regularly during the shift to be sure he was still alive. I was told that on the day shift he would sometimes be coaxed or forced upright and even to take a few steps and to eat and drink a little, but I never saw anything of the kind. One night he died that way, almost in a ball on the bed, and seemed just the same, except that his temperature was gradually several degrees too low.

And so it went. In a clinical way, there was often much to learn in such a setting. But I never got used to it. It was more like a house of horrors for me. After getting home, a fitful sleep would sometimes be haunted by these people and the circumstances in which they had to live.

There was a morgue in the basement of our building, cold even in the midst of Austin's worst heat spells and sporting more modern equipment than apparently was ready and available for the living. A goodly number of our patients wound up there. Around the morgue's work areas there was shelving. It contained large sealed jars with organs in preservative liquid. There were alcoholic's livers and brains, or the gray matter of people who had terminal syphilis, brains misshapen by huge tumors, smokers' lungs, and so forth, a rogue's gallery of pathology.

After our John Doe arrived on the ward, perhaps five minutes into my first shift, we took over from the EMS fellows and wheeled him down to the room the nurse had assigned. I was still just learning the ropes, of course. Jimmy was in charge of telling and showing me how to do the job. He and I had barely gotten acquainted when John Doe showed up. I was accordingly being taught the procedures initially using Mr. Doe as a willing or unwilling guinea pig.

Death on a Pale Horse by Turner, 1825-30 |

Mr. Doe did not seem to appreciate our needs and policy in this situation. He did not willingly give up his clothes, did not even seem to understand where he was and what we were about, accosting him in this way and trying to take his clothing. It seemed we might have to call the nurse to come give him a drug injection and so settle him down. I tried to calmly explain things to him, but he just was not getting it. We did manage to get him disrobed, though, and were, more or less all at once, involved in getting the gown on him, checking his pulse and his blood pressure, filling out the chart description on him, attempting to get from him his name and the name and phone number of any friends or relatives whom we might contact for him, and, given that he was resisting, taking a temperature rectally and getting ready to force a catheter up his penis, so he could pee properly into the jar at the base of the bed instead of all over the sheets we would otherwise have to change while he struggled, when, to our consternation, and evidently also very much to his, he began having a heart attack.

I had never seen anyone having one of those for real, not simply acting the role in a movie or on TV. I found witnessing it much more distressing than viewing it in a theater. The man looked terribly frightened, in great agony, and, quite convincingly, like he was about to die.

Between us, Jimmy realized first the significance of the John Doe's symptoms and, without giving me any instructions, ran down the hall toward the office to call the nurse. I was completely at a loss. Should I recline Mr. Doe more, crank the bed up straighter, talk soothingly to him, try to reassure him that everything would be OK, when clearly it would not, or do something else I could not guess?

I do not know if cardiopulmonary resuscitation had been worked out as a useful procedure for such situations by then. But I had not been taught CPR. Nor, it seemed, had Jimmy. There was no cardiac resuscitation machine available, such as the TV networks would later show in endless medical dramas, not even a handy EKG device.

The matter was soon moot. In probably less than two minutes from his first gasps and clutching at his chest, John Doe's face, till then contorted in obviously extreme pain, appeared to relax a bit. He took no more breaths, frightened, desperate, labored, or otherwise. I was certain he was dead from that moment and felt horrible. Jimmy and I had killed him. I could eventually somewhat excuse myself that it was perhaps just "the system," but we had been the instruments of its most macabre and deadly intervention into Mr. Doe's existence.

I heard the elevator doors and then Jimmy rushing back down the hall with our night nurse. She had been busy on a lower ward. After quick inspection, she confirmed my intuitive assessment. He was quite dead. She asked if we had gotten any information from him about next of kin or anyone else to contact. No.

She phoned the on-call doctor and explained the situation. He was calm and said he'd be over in a little while. She advised us to gather up Mr. Doe's things, put them in a personal items bag, and label them "John Doe," plus the night's date. The body also already had a little plastic bracelet labeled "John Doe" on one wrist. After a brief interview of Jimmy and me, she did a rapid completion of the chart to that point, and then went back to her duties downstairs.

When the doctor arrived, having taken awhile so that it was now a few hours later in our shift, he treated the matter as routine, signed off on the chart and, though there had obviously not been any autopsy to this point, nor any lab work done, other than the urine sample we'd taken and tested immediately after Mr. Doe arrived that showed apparent diabetes, and hardly even any communication with John Doe, he completed the death certificate, simply giving the cause as cardiac arrest.

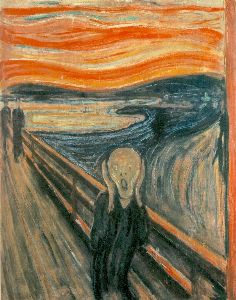

The Scream by Munch, 1893 |

He pointed out to me, the new guy, a curious thing about blood after someone dies, that it tends to collect toward the bottom of the body, drawn down by gravity and of course no longer circulated about equally, so that even though he was a Colored man, John Doe's body was now much lighter on top, but very dark, with purplish portions showing "livor mortis," in the lower parts of his feet, legs, back, and buttocks, though not where they were under pressure, in immediate contact with the bed.

The phenomenon, he said, is noticeable prior to the more commonly known "rigor mortis," a temporary stiffening that culminates at a somewhat later stage in the body's decomposition process. I took in the information even as I was appalled at the physician's detachment. But he, likely as not, was amused by what he saw as my too dramatic reaction to the death, and sought to give me a less naive perspective.

Once the doctor and nurse had left and our current work with the other patients was up to date, John Doe's body was put back on a gurney, the chart was added, shoved a little under so it would not fall during the trip, and I made my first of many treks with a corpse down to the well air conditioned morgue. It did not seem right to just leave Mr. Doe unattended there, but nobody would be on duty in that part of the facility till the day shift.

I remembered an incident when I was three and awake one evening in the back of our car. Rounding a rainy bend in a country road, suddenly there was a person in our way. He died apparently on impact with and tumbling over the vehicle, and though I had gotten out, seen him up close, a Black man, and knew that he was no longer living, I felt badly about our leaving his body alone on the road while Dad had gone off in the dark and on foot to get help, as Mom and I, feeling wretched, were waiting in the car at the accident scene.

After I had been working at the Austin State Hospital for a few weeks, I enlisted in the Army National Guard. I stayed on at ASH but served a monthly weekend drill or two with my new ARNG medical unit, at Camp Mabry in Austin, and then, starting about August, did a several month tour of active duty training, first at Fort Polk, LA. Following the state hospital experiences, military life was almost a piece of cake.